Edward IV became the King of England on March 4th, 1461 and was a member of the House of York. In 1464, he married Elizabeth Widville in a secret ceremony. Six years later, in November of 1470, Edward V was born as heir to the English throne. At the time that Edward was born, his father, was actually in exile in the “Low Countries” as Henry VI, a member of the house of Lancaster, had briefly been proclaimed King of England. However, Edward IV returned home in 1471 and reclaimed the English crown and named his son Edward Prince of Wales.

Because his father was in exile, Edward V was actually born in Westminster Abbey as his mother had sought sanctuary there. Three years later in August of 1473, his brother, Richard of Shrewsbury was born, and surprisingly his father did not have him named a prince but as a Duke of York.

The two brothers were not raised together, as Edward V was given his own household as a prince at Ludlow Castle in what is now Shropshire, England. Richard of Shrewbury was raised separately, possibly with his five sisters.

Edward V was only twelve when news reached him of his fathers death on the 14th of April, 1483. It is not known what King Edward IV died of but theories include pneumonia, malaria, apoplexy or even poisoning. After his fathers death, Edward V was assumed as King of England. Located at Ludlow Castle, Edward V did not immediately set out to London as his mother, Elizabeth Widville, was there to take power for him and to begin the planning for his coronation. It wasn’t until April 14th that Edward V, along with his uncle, the Early Rivers set off for London.

It is important to note that Elizabeth Widville did not notify her husband brother, Richard of Gloucester, of the king’s death. Instead, he found out about it from another party. Once he had heard of it, however, Richard of Gloucester set out to meet Edward V and ride in with him to London in order to support his transition over to king. So on Wednesday April 30th, Richard of Gloucester met Edward V at Stony Stratford, just north of London, and took guardianship of him.

When the entourage arrived in London, Edward V was established as the new King of England and his uncle, Richard of Gloucester was made the lord protector of the kingdom, as Edward was still so young. This was a disappointment to his mother who had been attempting to set herself up as the Regent for her young son, a tradition that was common in France, but not England at the time. And so, Elizabeth Widville sought sanctuary again in Westminster Abbey with her daughters and her son, Richard of Shrewbury.

When he arrived in London, the young king took up residence at the Tower of London, which was not only a prison but a royal castle. However, Richard of Gloucester did not stay with him at the Tower but at his mother’s residence elsewhere in London. In order to provide some company to the young king, Richard of Gloucester sent a delegation to Westminster Abbey to convince Elizabeth Widville to send the king’s brother, Richard of Shrewsbury, out of sanctuary to join his brother at the Tower. Eventually she complied and Richard of Shrewsbury joined Edward V at the Tower.

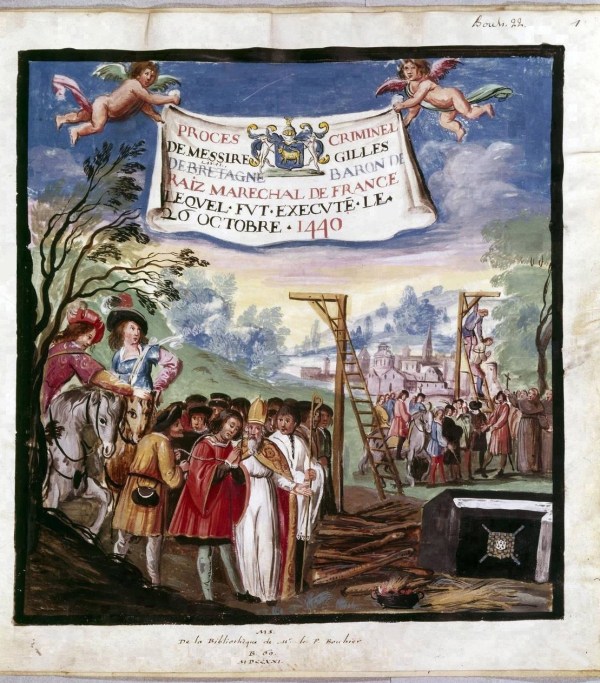

Originally, Edward’s coronation was set for May 4th, but Richard of Gloucester rearranged for it to be on June 24th so that the new king could open parliament on the following day. During one of the planning meetings at a royal council meeting held on June 9th, Bishop Stillington of Bath and Wells decided to address the royal council and claimed that Edward V could not be crowned as the King of England. Year earlier, before his marriage to Elizabeth Widville, King Edward IV has also been secretly married to a woman named Eleanor Talbot, a marriage that was supposedly performed by Bishop Stillington himself. Eleanor Talbot had also still been alive during Edward IV’s second marriage, thus making his marriage to Elizabeth illegitimate and all of his children bastards. This meant that Edward V had no rightful claim to the throne.

An unofficial parliament held that week declared that all of Edward IV’s and Elizabeth Widville’s children were illegitimate. After this was established, five days later Edward V’s uncle and protector of the realm, Richard of Gloucester was persuaded to become King of England.

On June 22nd, in order to make Richard III’s coronation more acceptable sermons were given out at Paul’s Cross and throughout London which raised publicly the issue of the bastardy of Edward V and his siblings. They also put forward what the Bible said should be done in respect of bastardy. On June 26th he was crowned King Richard III.

After Richard III’s coronation, supposedly a secret meeting was held between the Dukes of Hastings, Rotherham and Morton in which they discussed their disapproval of the removal of Edward V. Later at a parliament meeting, Lord Hasting’s supposedly attempted to attack Richard III (more likely he told him of his disapproval with hostility) and then: “The protector (Richard) cried out that a plot had been prepared against him, and they had come with concealed weapons, so that they could make the first attack. Then soldiers who had been stationed there by the lord, and the Duke of Buckingham, came running, and beheaded Hastings by sword under the name of treason.” The other two conspirators were imprisoned in Welsh castles.

A few weeks later, a supposed coup was being formed by the Duke of Buckingham. According to an early sixteenth century account called the Divisikroniek, “the Duke of Buckingham killed these children hoping to become king himself and this for the reason that he had read a prophecy about a future King Henry of England who would be very great and powerful, and he believed himself to be this for he was called Henry. And some say also that this Henry Early of Buckingham killed only one child and spared the other which he then lifted from the front and had him secretly abducted out of the country.” However, this was never proven.

Richard III, heard of the coup being planned and had the Duke of Buckingham captured and executed.

The fate of the two brothers, Edward V and Richard of Shrewsbury remains unknown, but it does appear that at least Edward V did die in the late summer of 1483, because after that date there is no documentation that he was ever seen again but there is also no documentation that he was ever put to death. Several documents do seem to point toward his death as he is referred to as the “late king” and as the “late son of Edward IV.” It is very possible that he died of illness as his doctor had been visiting the Tower to see him frequently. However, Richard of Shrewsbury seemed as healthy as a horse and was documented several times at being a gleeful boy.

There were also supposed plots and attempts to kidnap the boys from the Tower. Specifically, supposedly four men tried to abduct the two brothers from the tower by igniting diversionary fires around the Tower. However, they were captured and were tried at Westminster, condemned to death, drawn to Tower Hill and beheaded, and their heads were exhibited on London Bridge. No one knows why they were trying to get the boys, if they were, possibly for political reasons.

In 1485, King Richard III was killed at the Battle of Bosworth, afterwhich Henry VII of the House of Lancaster, eventually the House of Tudor, usurped the throne, which completely changed the political situation in England.

As soon as he had been crowned King of England, Henry VII imprisoned Bishop Stillington who had announced to the royal council that Edward IV had secretly married Eleanor so his marriage to Elizabeth was illegitimate. This was because Henry’s claim to the throne was weak and in order to strengthen it he wanted to erase the ruling that Edward IV’s children were illegitimate and marry Edward IV’s oldest daughter who would then again be the heiress of the House of York. This was accomplished when his first act of parliament was to destroy the act of parliament that declared them illegitimate.

However, this also meant that if either Edward V or Richard of Shrewbury was still alive they had an even better claim to the throne, meaning that Henry VII had an even better motive for killing the boys than anyone else. But, there is do evidence that they were alive then, or that he had them killed. In order to further the possibility that the boys were dead, from 1502 onward the official version of their life story stated clearly that both Edward V and Richard of Shrewbury were deceased, having been murdered nineteen years earlier, in 1483.

The Great Chronicle of London, which seems to have been completed in about 1512 cites three different rumours to the effect that the two boys may have been smothered in their feather beds, or possibly they were drowned in malmsey wine, or maybe they were poisoned.

The version of the story that has been the most upheld, but is likely the least factual, was written by Thomas More who was actually only five years old when the events actually occurred. He claims that: “Sir James Tyrell devised that they should be murdered in their beds, to the execution whereof he appointed Miles Forest, one of the four that kept them, a fellow fleshed in murder before time….about midnight came into the chamber and suddenly lapped them up among the clothes – so bewrapped them and entangled them, kepping down by force the featherbed and pillows hard unto their mouths, that within a while, smores and stifled, their breath failing, they have up to God their innocent souls into the joys of heaven, leaving to the tormentors their bodies dead in the bed.”

Nearly two hundred years after the boys disappearance, the bones of two children were found underneath a set of stairs in the Tower of London. Believing that they were bones of the two lost princes they were place in an urn and interred in Westminster Abbey. However, no one knows for sure if those are the boys bones or even if they were murdered.

Bibliography

Ashdown-Hill, John. The Mythology of the ‘Princes in the Tower’. United Kingdom: Amberley Publishing, 2018.

Thornton, Tim. “More on a Murder: The Deaths of the ‘Princes in the Tower’, and Historiographical Implications for the Regimes of Henry VII and Henry VIII.” History 106, no. 369 (2021): 4-25.